- What is Neuro-ophthalmology?

- What specific conditions are typically managed by a Neuro-ophthalmologist?

- Toxic Optic Neuropathy from intake of anti-TB Drugs

- Optic Neuritis

- Double Vision from "muscle imbalance"

- Strokes and Brain Tumors

What is Neuro-ophthalmology?

If the human eye works like a camera, we can imagine that the "processing of the film" into what we see as visual images is transmitted by the optic nerves from the globe of the eye, to their visual pathways in the brain and finally towards the visual processing centers at the back part of the brain. This is the realm of a Neuro-ophthalmologist, i.e., an eye specialist with special interest in the eye manifestations of diseases or injuries of the optic nerves and visual pathways (everything behind the eye involved in the visual process). Included in this field are brain pathways and processes involved in the control of eye movements. Several neuro-ophthalmic symptoms are also manifestations of systemic conditions like hypertension, diabetes, stroke, cardiovascular diseases, multiple sclerosis, brain tumor, and many others.

What specific conditions are typically managed by a Neuro-ophthalmologist?

Some common neuro-ophthalmic conditions affecting vision include optic neuritis and toxic optic neuropathy (from intake of anti-TB medications); while examples of those affecting eye movements are cranial nerve strokes and thyroid disease. Patients with eye problems secondary to brain tumors or strokes, as well as migraines are also commonly seen in the neuro-ophthalmologist's clinic.

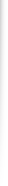

Optic Neuritis

Optic neuritis is an inflammatory condition of one or both optic nerves causing decreased vision, accompanied by changes in color perception and contrast sensitivity. These symptoms are usually rapid and progress in days, ranging from mild to severe, and usually accompanied by eye pain or pain on eye movement. In temperate countries, optic neuritis is commonly associated with a neurologic condition called multiple sclerosis. In the Philippines, a vast majority of cases have no identifiable cause (presumed to be secondary to occult infections). On a case-to-case basis, intravenous steroid therapy may be beneficial in some patients.

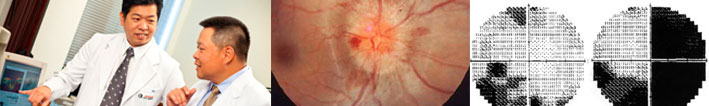

Toxic Optic Neuropathy from intake of anti-TB Drugs

Tuberculosis is still a major problem in a developing country like the Philippines. Especially in rural areas, triple or quadruple anti-tuberculosis medications are rampantly prescribed, with poor compliance in many cases leading to over or under-medication. Unfortunately, some of these drugs, most notably Ethambutol and Isoniazid have a propensity for causing toxicity to the optic nerves. As with many optic nerve conditions, damage caused by these drugs may be irreversible and some permanent loss of vision or color perception persists despite discontinuation of medication intake. This does not suggest that patients stay away from these drugs at all. The systemic benefits of these drugs in patients with tuberculosis outweigh the small risk of toxicity. Ideally however, patients who are about to start anti-TB medications should visit an ophthalmologist who will take baseline measurements of visual function. These tests are repeated every 1-2 months to watch out for the earliest signs of toxicity so that the prescribing internist may be advised accordingly.

Double Vision from "muscle imbalance"

(a) Cranial Nerve "Stroke"

One or more muscles controlling eye movements may occasionally be weakened by an infarction of their corresponding nerve supply. The resulting muscle imbalance may lead to symptoms like double vision and drooping of the eyelid. Many cases are benign and are caused by systemic conditions like diabetes and hypertension. They usually resolve spontaneously in 3-12 months without any treatment. Some may be caused by more innocuous conditions (see below).

(b) Thyroid Disease

Thyroid disease can manifest in the eye with or without the clinical presence of hyperthyroidism. Symptoms include proptosis ("eyeballs seem to pop out of their sockets"), double vision, eyelid retraction ("frightened appearance"), red/congested eyes, and blurred vision. Depending on the severity of symptoms, a wide range of treatment options is available and can range from plain medical therapy to surgical procedures.

Strokes and Brain Tumors

As vast areas of the brain are involved in the overall function of the visual system, injuries from strokes or brain tumors affect vision and eye movements in various ways depending on the extent and location of the lesion. These include loss of vision (often described as loss of a particular field of vision, say, peripheral areas or one-half of the visual field), and "muscle imbalance" with inability to move the eye to a particular position, leading to double vision. Several post-stroke patients may also have visual perception difficulties, meaning the visual pathway may be intact, but the processing of the information is affected (the patient may not "understand' what he sees). Occasionally, patients with neuro-ophthalmic signs and symptoms from brain tumors are initially seen by the ophthalmologist, who then makes the crucial primary diagnosis and subsequent referral to a neurosurgeon. Ideally, the neuro-ophthalmologist, neurologist, and neurosurgeon should all be involved in the long term management and care of these patients (as well as in many other neuro-ophthalmic conditions).

If the human eye works like a camera, we can imagine that the "processing of the film" into what we see as visual images is transmitted by the optic nerves from the globe of the eye, to their visual pathways in the brain and finally towards the visual processing centers at the back part of the brain. This is the realm of a Neuro-ophthalmologist, i.e., an eye specialist with special interest in the eye manifestations of diseases or injuries of the optic nerves and visual pathways (everything behind the eye involved in the visual process). Included in this field are brain pathways and processes involved in the control of eye movements. Several neuro-ophthalmic symptoms are also manifestations of systemic conditions like hypertension, diabetes, stroke, cardiovascular diseases, multiple sclerosis, brain tumor, and many others.

What specific conditions are typically managed by a Neuro-ophthalmologist?

Some common neuro-ophthalmic conditions affecting vision include optic neuritis and toxic optic neuropathy (from intake of anti-TB medications); while examples of those affecting eye movements are cranial nerve strokes and thyroid disease. Patients with eye problems secondary to brain tumors or strokes, as well as migraines are also commonly seen in the neuro-ophthalmologist's clinic.

Optic Neuritis

Optic neuritis is an inflammatory condition of one or both optic nerves causing decreased vision, accompanied by changes in color perception and contrast sensitivity. These symptoms are usually rapid and progress in days, ranging from mild to severe, and usually accompanied by eye pain or pain on eye movement. In temperate countries, optic neuritis is commonly associated with a neurologic condition called multiple sclerosis. In the Philippines, a vast majority of cases have no identifiable cause (presumed to be secondary to occult infections). On a case-to-case basis, intravenous steroid therapy may be beneficial in some patients.

Toxic Optic Neuropathy from intake of anti-TB Drugs

Tuberculosis is still a major problem in a developing country like the Philippines. Especially in rural areas, triple or quadruple anti-tuberculosis medications are rampantly prescribed, with poor compliance in many cases leading to over or under-medication. Unfortunately, some of these drugs, most notably Ethambutol and Isoniazid have a propensity for causing toxicity to the optic nerves. As with many optic nerve conditions, damage caused by these drugs may be irreversible and some permanent loss of vision or color perception persists despite discontinuation of medication intake. This does not suggest that patients stay away from these drugs at all. The systemic benefits of these drugs in patients with tuberculosis outweigh the small risk of toxicity. Ideally however, patients who are about to start anti-TB medications should visit an ophthalmologist who will take baseline measurements of visual function. These tests are repeated every 1-2 months to watch out for the earliest signs of toxicity so that the prescribing internist may be advised accordingly.

Double Vision from "muscle imbalance"

(a) Cranial Nerve "Stroke"

One or more muscles controlling eye movements may occasionally be weakened by an infarction of their corresponding nerve supply. The resulting muscle imbalance may lead to symptoms like double vision and drooping of the eyelid. Many cases are benign and are caused by systemic conditions like diabetes and hypertension. They usually resolve spontaneously in 3-12 months without any treatment. Some may be caused by more innocuous conditions (see below).

(b) Thyroid Disease

Thyroid disease can manifest in the eye with or without the clinical presence of hyperthyroidism. Symptoms include proptosis ("eyeballs seem to pop out of their sockets"), double vision, eyelid retraction ("frightened appearance"), red/congested eyes, and blurred vision. Depending on the severity of symptoms, a wide range of treatment options is available and can range from plain medical therapy to surgical procedures.

Strokes and Brain Tumors

As vast areas of the brain are involved in the overall function of the visual system, injuries from strokes or brain tumors affect vision and eye movements in various ways depending on the extent and location of the lesion. These include loss of vision (often described as loss of a particular field of vision, say, peripheral areas or one-half of the visual field), and "muscle imbalance" with inability to move the eye to a particular position, leading to double vision. Several post-stroke patients may also have visual perception difficulties, meaning the visual pathway may be intact, but the processing of the information is affected (the patient may not "understand' what he sees). Occasionally, patients with neuro-ophthalmic signs and symptoms from brain tumors are initially seen by the ophthalmologist, who then makes the crucial primary diagnosis and subsequent referral to a neurosurgeon. Ideally, the neuro-ophthalmologist, neurologist, and neurosurgeon should all be involved in the long term management and care of these patients (as well as in many other neuro-ophthalmic conditions).